How ‘Pee-wee’s Playhouse’ influenced a generation of kids-at-heart

Somehow, amid all the colorful claymation and puppetry, the human character at the center was the most animated of all.

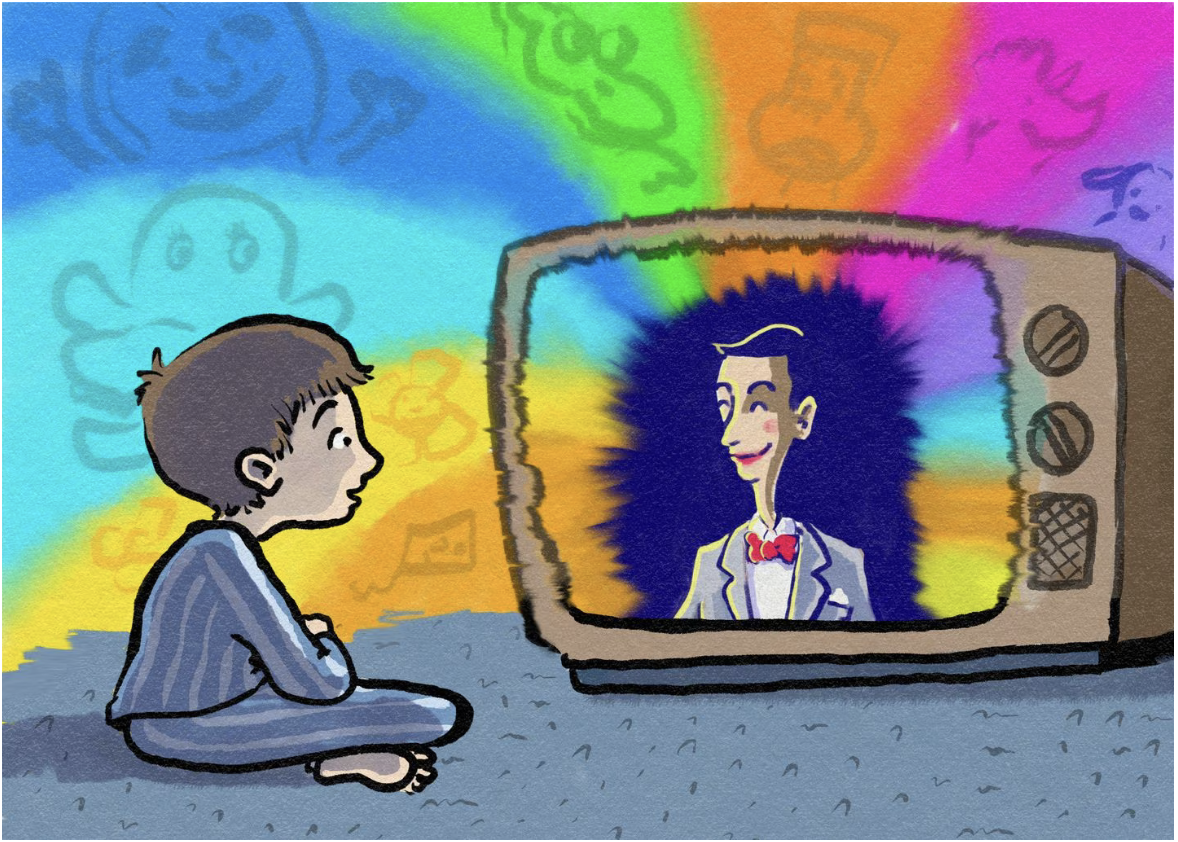

I spent many Saturday mornings sitting on the living room carpet in my grandparents’ house in front of the television set, belly filled with sugary cereal, eyes glued to the screen as I watched the usual parade of cartoons. But one Saturday in 1986, CBS rolled out something completely different: “Pee-wee’s Playhouse.”

A utopia of claymation creatures, including a flying pterodactyl and a snowman, filled the screen to the tune of calming tropical music. The titular playhouse appeared on the horizon, and just as I entered a meditative state, the camera rocketed toward the playhouse doors, plummeting me into a live-action, Technicolor acid trip.

That’s when I first heard the shrill voice belting out the show’s theme song introducing Chairry (an armchair), Globey (a globe with a French accent), and Conky (a robot) — and inviting me “to go wacky, at Pee-wee’s Playhouse!”

Somehow, amid all the colorful claymation and puppetry, the human character at the center was the most animated of all — this man-child in the too-small gray suit prancing and mugging for the camera as he took us through his playhouse.

“What in the world did I just watch?” I recall thinking when the opening ended. Whatever it was, it was for me — I was 9 years old and had never seen anything like it.

Later, my friends and I watched Tim Burton’s “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” on home video, constantly stopping the tape to rewind to moments we’d missed because we’d been laughing so hard at lines like, “You don’t wanna get mixed up with a guy like me. I’m a loner, Dottie. A rebel.” Large Marge scared the daylights out of me.

My inner child took a gut punch when I learned Paul Reubens died July 30. When “Playhouse” debuted, I was a kid surrounded by very real adult problems. My grandparents were raising me since my mother was incarcerated because of missteps related to her heroin addiction. I had yet to meet my father. “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” offered surreal escapism.

I was raised in Worcester, surrounded by all things Patriots, Bruins, Celtics, and Red Sox. Growing up in a sports-obsessed culture wasn’t easy for a boy who preferred to sit quietly at his drawing table. I was considered effeminate (until I arrived at art school and was considered a jock), and effeminate boys didn’t have many men to look up to when I was a kid. Our role models were action heroes, like Sly Stallone, and star athletes like … I don’t know, Wayne Gretzky? But Pee-wee showed us that we could be ourselves without apology. He was goofy — the antithesis of Rambo and the violent action heroes that dominated the multiplex.

Pee-wee taught me that it was OK to carry into adulthood juvenile things that made me happy. My art studio is filled with many of the action figures and puppets I played with as a kid: Fraggles, Muppets, Autobots, Ghostbusters. I know many other illustrators who have similar collections, and I believe we keep these vintage toys on hand because it’s how we first learned to tell stories. I could watch the Smurfs on TV, but I could use my Smurfs figurines to direct my own Smurfy adventures.

I also have a few unopened Playhouse toys, which I purchased in 1991, the day news broke about Reubens’s arrest for indecent exposure in a public movie theater. I was an enterprising eighth-grader who knew those figurines wouldn’t be on toy shelves for much longer and might be worth money someday.

All these years later, I still haven’t parted with my pre-packaged Globey, Randy, Jambi, and Puppet Land Band. Through the lens of time, I can see that, perhaps, Reubens was treated unfairly. But I am still left wondering — what the hell was he thinking?

“Pee-wee’s Playhouse” was subversive — so familiar, yet so punk. The thing about childhood is that you don’t really understand how the media you consume is influencing and inspiring you as it’s happening. You need to wait to grow up before you’re able to connect the dots (“la, la, la, la”). So when I look at my body of work, illustrated literature for young people, I can see the connections. In my picture book “Punk Farm,” a seemingly quaint farm becomes the setting for a raging rock show put on by the barnyard animals — so familiar, yet so punk. Reubens watched “Howdy Doody” and “Captain Kangaroo” while growing up in Sarasota, Fla., known for being the winter quarters of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Connect the dots.

Raina Telgemeier, the graphic novelist behind middle-grade books like “Smile,” “Sisters,” and “Drama,” is a friend who also connects the dots of her own work to Reubens’s influence. “‘Pee-wee’s Big Adventure’ was released when I was 8 years old, right after my youngest sibling was born,” she told me. “At a time when my family expected me to be the ‘good’ oldest sister, along came Pee-wee Herman: a role model in silliness, play, and whimsy.” He was proof that “you can be the adult who is loyal, wise, and runs into burning buildings,” she said, “and also be the weirdo who revels in art, dress-up, and dinosaurs.”

Like SpongeBob, Pee-wee Herman was an adult, but not really an adult. Sure, he could legally drive the ice cream truck, though he’d be more likely to gleefully run out to the street with spare change upon hearing its familiar jingle. I see that ecstatic quality in my graphic-novel character Lunch Lady. She is a cartoonish adult who kids can befriend, wears a uniform (just like Pee-wee), and also has an arsenal of silly catch phrases like “Holy guacamole!” and “That just mashes my potatoes!”

Mindy Thomas, cohost of the podcast “Wow in the World,” strikes a similar tone via her audio adventures. “Our characters aren’t pretending to be kids, but they’re not burdened by any of the responsibilities that come along with being adults, either,” she told me. “My character, ‘Mindy,’ lives in a gingerbread mansion of her own design, has a giant pigeon for a pet, gets around in an ice cream truck, has access to all of the caviar sandwiches she can stomach, and exists in a world where imagination (and occasionally buttons) is really the only currency.”

Reubens also influenced Brad Montague, creator of the viral video series “Kid President.” “There are handmade pieces in every frame of ‘Pee-Wee’s Playhouse.’ That’s something I very much worked to do when creating ‘Kid President,’” Montague told me, also noting that “one of the great gifts of art is that it can help people feel less alone, and Paul Reubens did that.”

A shared sense of childhood nostalgia and wonder is now the bedrock of my marriage. My wife, Gina, and I both celebrate the pop culture that inspired our imaginations as kids — she with Popples, Cabbage Patch Kids, and Rainbow Brite. We also share a love of camp, which we honor via an annual Christmas drag brunch hosted by our friendly neighborhood drag performer, Hors D’oeuvres.

During lockdown, that IRL joy was taken away, so we rewatched 1988′s “Pee-wee’s Playhouse Christmas Special.” As kids, we had no idea how revolutionary and inclusive the show was at the time — but as parents, we couldn’t wait to share it with our three kids for that reason. “Jingle Bell Rock” is performed by k.d. lang; and Whoopi Goldberg, Joan Rivers, Cher, Grace Jones, Little Richard, Magic Johnson, Zsa Zsa Gabor, the Del Rubio Triplets, Charo, and more all join the regular Playhouse players.

As Latin Grammy and Emmy award-winning musician Lucky Diaz put it, “‘Pee-wee’s Playhouse’ was the first acceptable ‘alternative lifestyle’ I saw: ‘We can be this and not be judged?’”

In 2010, Gina and I saw the Broadway revival of the original Pee-wee Herman show. We sat front row center. Chairry hadn’t changed much, but under the stage makeup Reubens looked like an aging man.

At the end, when the actors took their final bows, I shouted out, “Thank you, Pee-wee!” And Reubens, in his full Pee-wee garb, mouthed “thank you” back.

Paul Reubens was 70 when he died, but Pee-wee Herman always seemed ageless. Perhaps that’s why so many of us fans were in shock to hear his creator had been mortal after all.

Jarrett J. Krosoczka is a National Book Award finalist for “Hey, Kiddo” and the New York Times best-selling graphic novelist of the Lunch Lady series. His latest graphic memoir, “Sunshine: How One Camp Taught Me About Life, Death, and Hope,” was published in April.